The

NEVADA DUSTERS

The Story of a Major League Baseball Franchise

|

HOW MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL CAME TO LAS VEGAS

|

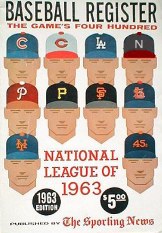

The Nevada Dusters (represented in

the top row, right) join the ranks of the NL

In Las Vegas in the late Fifties, a former major league ballplayer turned oilfield millionaire named Conn Hudson had tried to interest the NL in placing a team in Nevada. Instead, the National League established expansion teams in Houston and New York in 1960 to foil the designs of the Continental League. Branch Rickey, front man for the Continental League, had wanted Hudson to throw in with the insurgent circuit, but Hudson refused. His franchise would be in the NL or the AL, or it wouldn't exist, period. He began to cast about for an existing team to buy and relocate, and he soon set his sights on the Milwaukee Braves. Confident in the ultimate success of his endeavor, Hudson even financed the building of Horizon Field, a state-of-the-art ballpark on the southwestern outskirts of Las Vegas. Horizon Field, finished in mid-1962, was hailed by many as "Hudson's Folly."

According to Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella in Total Ballclubs (2005), "The honeymoon between the [Braves] and the Milwaukee community started to end around the same time that the Braves began to realize that not every October would be spent playing the Yankees in the World Series. In particular, two latent issues that had been smoothed over during the halcyon years came to the fore with increasingly bitter stress, especially in the writings of influential Milwaukee Journal sportswriter Russ Lynch. The first had to do with the fact that [majority stockholder Lou] Perini, for all his local honors of having brought the franchise to Milwaukee, had remained very much an absentee owner, continuing to reside near his other business interests in Massachusetts. For critics like Lynch, this made it impossible to completely trust the team owner and in fact perpetuated a threat that, for the sake of the bottom line, he might one day shift the club out of Milwaukee as abruptly as he had moved it in. In this context, Lynch and others noted the growing role played by television in the ledgers of a baseball franchise and Milwaukee's scant potential in this area. Another sore point, made more and more important in the push to get Perini either to sell the team to local interests or move his base of operations to Wisconsin, was the team's policy of forbidding fans to bring beer into County Stadium, forcing them to purchase it from ballpark concessionaires. The issue was aired to full censorious effect and, together with the team's relatively more humdrum play on the field, lessened enthusiasm for the Braves at the turnstiles."

With "the attendance falling as rapidly as the batting averages of some of the veterans" and stung by all the criticism, Perini sold the Braves to Hudson at the end of the 1961 season. But he could not remove himself from controversy quite that easily. As Dewey & Acocella write: "Led by a group headed by future Milwaukee Brewers president and future commissioner Bud Selig" city interests sued Perini for failing to consider local buyers for the franchise. Attorney -- and future commissioner Bowie Kuhn represented the NL, which had approved the sale, and Perini and the league eventually prevailed in the lawsuit.

Conn Hudson had his franchise. But with it came a $28,000,000 team salary, which was more than he could afford. Hank Aaron alone commanded a $4,800,000 salary in 1962. It was generally acknowledged that Eddie Mathews, Warren Spahn, Joe Adcock and Lew Burdette, among other former Braves, were on the downside of their major league careers. Hudson wanted a fresh start for the new franchise. With that goal in mind, and building for the future, he set about making trades that would fundamentally alter the makeup of both leagues. Of the 35 players on the Braves roster the day he bought the franchise, Hudson would keep only a handful.

Several Braves pitcher became Nevada Dusters. There were starters Bob Shaw and Tony Cloninger. Shaw had gone 12-14 in 1961 with the White Sox and the Athletics, while Cloninger had a record of 7-2 with a 5.25 ERA the previous season. Also remaining with the club were Jim Constable, who had been a AAA pitcher in '61 and Claude "Frenchy" Raymond, who had gone 1-0 with two saves for the Braves. A key -- and controversial -- trade was the departure of Warren Spahn and Lew Burdette to Baltimore for Steve Barber (18-12, 3.33 in 1961) and a 19-year-old rookie southpaw named Dave McNally. Spahn had been an All-Star pitcher for years, and Burdette had been named World Series MVP in 1957. But trading them shaved over $4,000,000 from the payroll, and Duster scouts believed Barber and McNally had bright futures. The trade with the White Sox that sent Denny Lemaster to Chicago in return for Joe Horlen was made solely based on Hudson's preference for Horlen. Relief pitchers Bobby Locke, Bob Duliba, Jim Brewer and Bill Dailey joined Raymond and Constable in the bullpen. Minor league pitching prospects such as Jim Bouton, Jim Roland, Pete Richert, Bruce Howard and Marcelino Lopez gave the Dusters a plethora of young talent.

As for hitters, Hudson's decision to trade away Hank Aaron remained the talk of the baseball world for quite some time. There were several facets to the decision: Aaron's disinterest in moving to Nevada and his price tag -- which Hudson did not feel he could afford -- being chief among them. Hudson acquired a young slugger named Billy Williams (25, 76, .278 in 1961) from the Chicago Cubs in exchange for Hammerin' Hank. Also part of the Aaron trade was middle infielder Ken Hubbs, a rookie phenom that Hudson expected would play a key role in the franchise's future. The New York Yankees were so happy to acquire third baseman Eddie Mathews that they parted with third baseman Clete Boyer, middle infielder Tom Tresh, outfielder Hector Lopez and $1,000,000. As for Mathews, the consensus among the Dusters' scouts was that he was past his prime -- a judgment that would prove them fallible. In this case it wasn't about saving money, as Boyer's salary exceeded that of Mathews. Hudson believed he was getting three quality players in exchange for one. An identical motive lay behind the trade of catcher Joe Torre to Pittsburgh for three minor league prospects -- first baseman Donn Clendenon, third baseman Bob Bailey, and middle infielder Gene Alley. Nevada and Minnesota exchanged veteran first basemen, with Joe Adcock joining the Twins and Vic Power becoming a Duster. Second baseman Jerry Adair was acquired from Baltimore, and catcher Johnny Blanchard from the Yankees. Outfielder Tony Oliva and first basemen Tony Perez and Wes Parker were highly-regarded minor league prospects acquired by Nevada. Only outfielders Mack Jones, Lee Maye and Hawk Taylor remained from the Milwaukee Braves roster.

Another factor that entered into Hudson's decisions was that the contracts of Spahn, McMahon, Buhl, Willey and Adcock expired after the 1962 season. He knew that even if he kept them for one season he would not be able to afford them in the future. On the other hand, all but five of the players on the Nevada Dusters 25-man roster had contracts extending beyond the '62 season.

Hudson succeeded in trimming over $7,000,000 from the team payroll. Even so, most baseball pundits predicted the Nevada Dusters would be in the red by the end of 1961. According to those same pundits, Hudson had given away most of his offense -- Aaron and Mathews in particular -- and significantly weakened the pitching staff with the departures of Spahn, Lemaster, Burdette and Bob Buhl. So said the experts. But Hudson wasn't worried. He had a team filled with young talent, players who were, for the most part, excited about being charter members of a brand new franchise The prognosticators opined that the Nevada Dusters would be extremely fortunate to break even their first year. Hudson predicted his club would do better than .500.

But this was, after all, the game of baseball. Which meant that no one could really predict with any accuracy what was about to happen....

|